Table of Contents

The Gospel and the Apostles:

A - The Synoptic Problem:

B - The Gospel of John:

C - The Apostolic Letters:

Communal Truth:

- APPENDIX

- Pages:

- 1 - Introduction

- 2 - Patristic Evidence

- 3 - Common Synoptic Material

- 4 - Displaced Triple Tradition

- 5 - The Double Tradition as per Q

- 6 - Mark as per Griesbach

- 7 - The Writing of Luke

- 8 - The Translation of Matthew

- 9 - Clarifying Verses Added to Matthew

- 10 - Semitic Matthew

- 11 - An Essay on the Prologue of John

- 12 - Bibliography

Appendix - Page 11

On the So-Called Prologue of John

Clearly, there have been interpolations at certain points in New Testament texts. Some of the best examples are found in the Johannine writings. John 5:4, describing an angel coming down to stir up the waters in the pool of Bethesda, does not appear in the earliest manuscripts. Rather it seems to have been added by a later copyist as an explanation for the sick man’s complaint in verse 7. Similarly, I John 5:7 (“There are three witnesses in heaven: the Father, the Word, and the Holy Spirit...”) appears only in the Vulgate. While a valid statement of the early church’s belief in the Trinity, it was certainly not a part of the original text. At least one longer example also exists, the story of the woman caught in adultery in John 8. And although there is no textual evidence for its exclusion, the final chapter of John’s Gospel bears some signs that it may have been a later addition to the original version of the book, which seems to come to a satisfying conclusion with chapter 20.

But what about the first 18 verses of John, the so-called “Prologue”? Many scholars believe that it was also a later addition, or alternatively that it existed at one time as a separate entity and was then incorporated into the Gospel by the author. Regardless, it seems to be universally viewed as a distinct passage, separate from the rest of the Gospel, or at least separate from the rest of the first chapter of the Gospel. Virtually every outline of the structure of John lists this “Prologue” as a separate section, with verse 19 beginning a new passage.

In this essay, I would like to challenge this division. I will not attempt any sort of history of the scholarship regarding John’s Gospel, nor deal with the arguments in favour of such a division, but rather simply give my own arguments for why I believe the “Prologue” to be integral to the author’s discussion of John the Baptist in the rest of chapter 1, and why these two “sections” cannot be separated from one another.

My consideration of this matter was sparked by the opinion of some scholars that verse 15 in particular was “probably an interpolation” since it seems to break the flow of the passage and seems to be basically a displacement of verse 30. And indeed, in support of this, the New Revised Standard Version places verse 15 in parentheses. But does such a judgement hold up? Unlike the interpolations mentioned earlier there is no textual evidence that verse 15 does not belong where it is, plus there is a crucial difference between the type of interpolations described earlier and this type of hypothetical interpolation.

In all of the earlier examples, additions were made in order to make the text clearer. However, John 1:15 (as well as countless other interpolations proposed at many times and in various ways) makes the text less clear. The proposal of an interpolation as an explanation for a difficult passage seems to me to be extremely problematic. It requires such an addition to be either accidental or one which ignores the text around it. Of course, copyists can make mistakes, but interpolations of this sort seem often to be an “easy way out” whenever a difficult passage is encountered which does not fit a particular theory’s interpretation. Instead of dealing with such a text when it does not make sense to us, it is very tempting to simply dismiss it as an interpolation. Such theorised additions also violate “Occam’s Razor” by “multiplying entities”, adding extra steps into the production of a certain text, instead of simply accepting that this is the text we have and that it is worded as the author intended. So rather than providing answers to textual problems, perhaps such proposed interpolations ought to be clues to us that we are just not understanding the author’s intentions or style.

Taking John 1:15 as such a clue, then, I decided to take another look at what is going on in the first chapter of this Gospel, paying particular attention to the style of writing which is characteristic of Johannine literature. Unlike Paul and the Synoptic authors, John does not often deal with his material in a straightforward exposition of point after point. Instead, he [or they - this essay will not consider whether all the Johannine literature is by the same author, but it does all share a similar style] typically employs what might be described as a “spiralling” style: A topic is introduced, then additional elements are added to the main theme. As each new element is added, it is dealt with in relation to the main theme and with the other elements already introduced. The author therefore often returns to material he has already written, now seen in the new light of the extra element. With each “pass” the spiral becomes wider in its sweep, and deeper in its meanings. There is therefore frequently a great deal of repetition in this style, but this repetition is never static, but becomes progressively more encompassing as it spirals outward.

The best example of this spiralling style is probably the entire First Letter of John, which is one continuous spiral, but which might be described as an elliptical spiral since it has two major foci: belief in Jesus and love for fellow Christians. The author alternates his emphasis on each of these two themes as new elements are added, showing how they are to be equated, and how they are to be lived out within the Christian community.

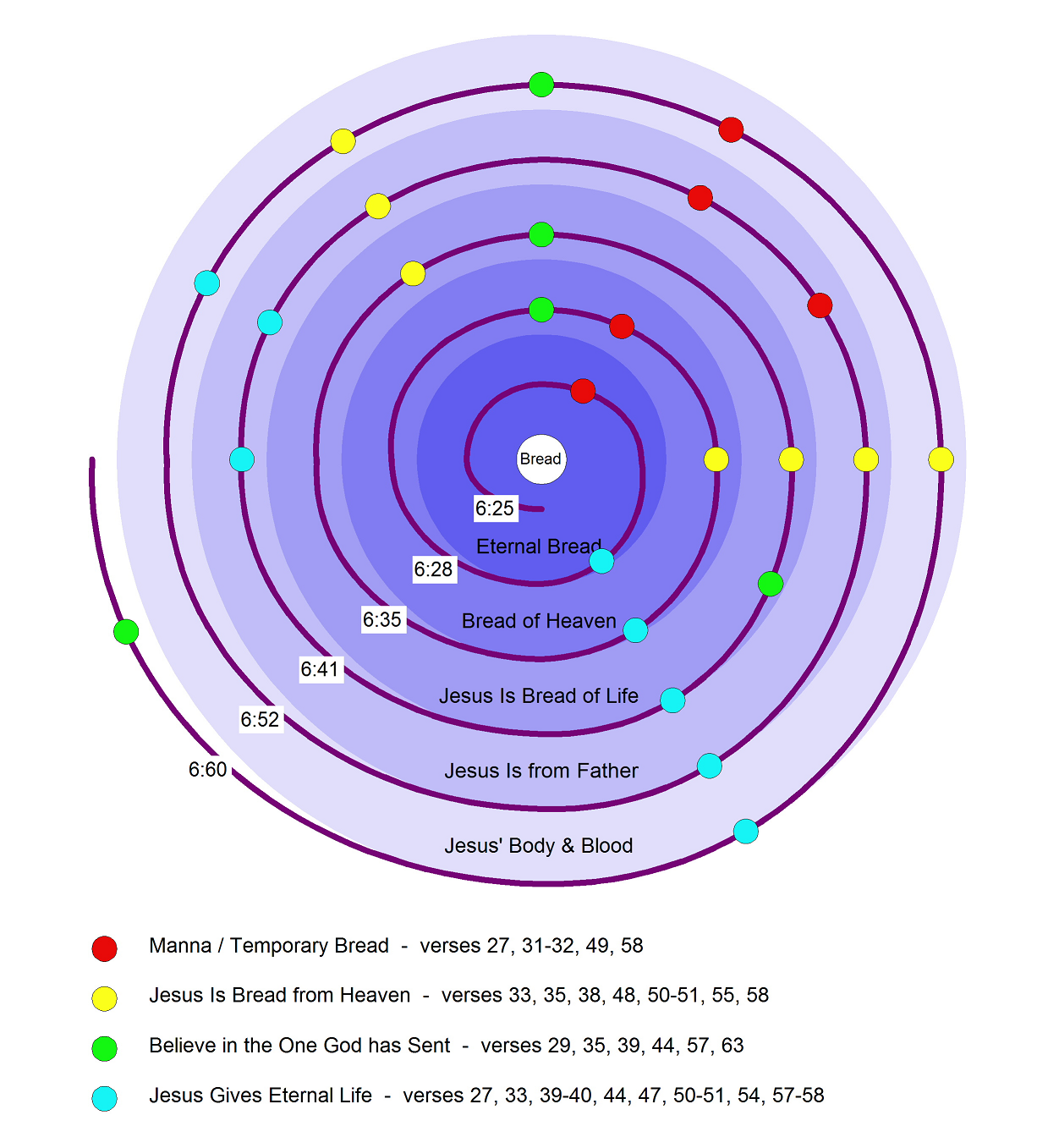

There are also a number of passages within John’s Gospel which follow a similar spiralling pattern, such as in Jesus’ lengthy “Farewell Discourse” in chapters 13 to 16. A shorter, and hence perhaps clearer example is the “Bread of Heaven” passage in John 6:25-59, which may serve to help us see in more detail how this pattern functions. [Here again, however (as with nearly every passage in John), there is much scholarly debate about the origin and integrity of this particular passage, which this essay will not attempt to address. We will simply read it as it now stands within John’s Gospel.]

At the beginning of this passage, after the Feeding of the Five Thousand, Jesus warns his hearers not to “work for food which spoils, but for food which endures to eternal life” (verse 27). This presents the main theme of this “spiral”, the eternal Bread of Heaven. A brief exchange then ensues in which Jesus encourages his audience to “believe in the one whom God has sent” (verse 29) and his antagonists refer to the manna in the wilderness as the “bread of heaven” (verse 31). John often uses comments or questions from others as the means of injecting the new elements into his spiral, and this is the case here. It allows the theme to be developed (in verse 33) in terms of the contrast between the manna described in the Torah (which was temporary, and did spoil) and the true bread of heaven. John has thus retraced his steps through verse 27, but now with all the added meanings of the intermediate verses added in.

In John’s next pass around the spiral (verses 35 to 40), Jesus identifies himself as the true Bread of Heaven, and all of the elements are re-examined in this light: He is the one whom God has sent, the one to be believed in, and for those who do believe he will give eternal life. Then again, Jesus’ antagonists object, this time to Jesus’ claim that he “came down from heaven” when he is just a man. This leads into the next circle (verses 41 to 51), where Jesus discusses his relationship with God and how God “draws” those who believe. Then again a number of the themes are reviewed in light of this new element: Jesus is the bread of life, and will raise up those who believe in him to eternal life. He repeats that those who ate the temporary manna did die, but that those who eat the true bread of heaven will not die. Jesus ends this pass with the shocking statement that the true bread of heaven is his own “flesh”, resulting again in the objections of his antagonists.

The final pass around the spiral in this passage (verses 52 to 59), picks up this last element of eating and drinking Jesus’ flesh and blood, and yet again we hear that this is the true bread of heaven sent by God the Father, that those who eat it will be raised to eternal life, but that those who ate the manna died. Verse 58 especially gives a summary of all the major themes discussed in the spiral. After the initial statement of the theme in verse 27, then, there have been four full sweeps around a spiral in this passage, and in each case most of the same themes have been repeated, but each time with added meaning. Nor does the passage end here. The rest of the chapter deals with the theme of those who have been drawn by God to Jesus, picking up again on elements touched on in the passage discussed, but the spiral has become much looser now, allowing the text to move on to additional topics.

This very brief discussion, however, should suffice to display the spiralling pattern John is following. And, of course, many of the themes present in this spiral are found throughout the Johannine corpus (for instance, the theme of “believing in the one whom God has sent” has already been identified as one of the main foci of I John). Each “spiral” we might identify, then, is not an isolated entity, but is part of the entire matrix of John’s Gospel, which if we were to attempt to chart out all its connections would be a complex interwoven three- (or more-) dimensional web of spirals, eddies, and threads, and every reading might potentially reveal even more connections. But this brief excursion into John 6 demonstrates that such a spiralling pattern is a characteristic of the Johannine style, and that it is valid to look for a similar pattern elsewhere.

And although this is a free-flowing, fluid style, rather than a rigid, mechanical one, the following is an attempt to portray the spiral in John 6 visually, with “Bread” placed at the centre, representing the focus of this spiral. The sweeps around the spiral are shown as concentric blue circles, through which the spiral itself passes, with each circle labelled at the bottom with a phrase suggesting the new element introduced during that sweep. The verse with which each new sweep begins is also indicated. Along the spiral itself appear different coloured points, representing where the author has chosen to deal with his recurring themes, as listed at the bottom of the diagram:

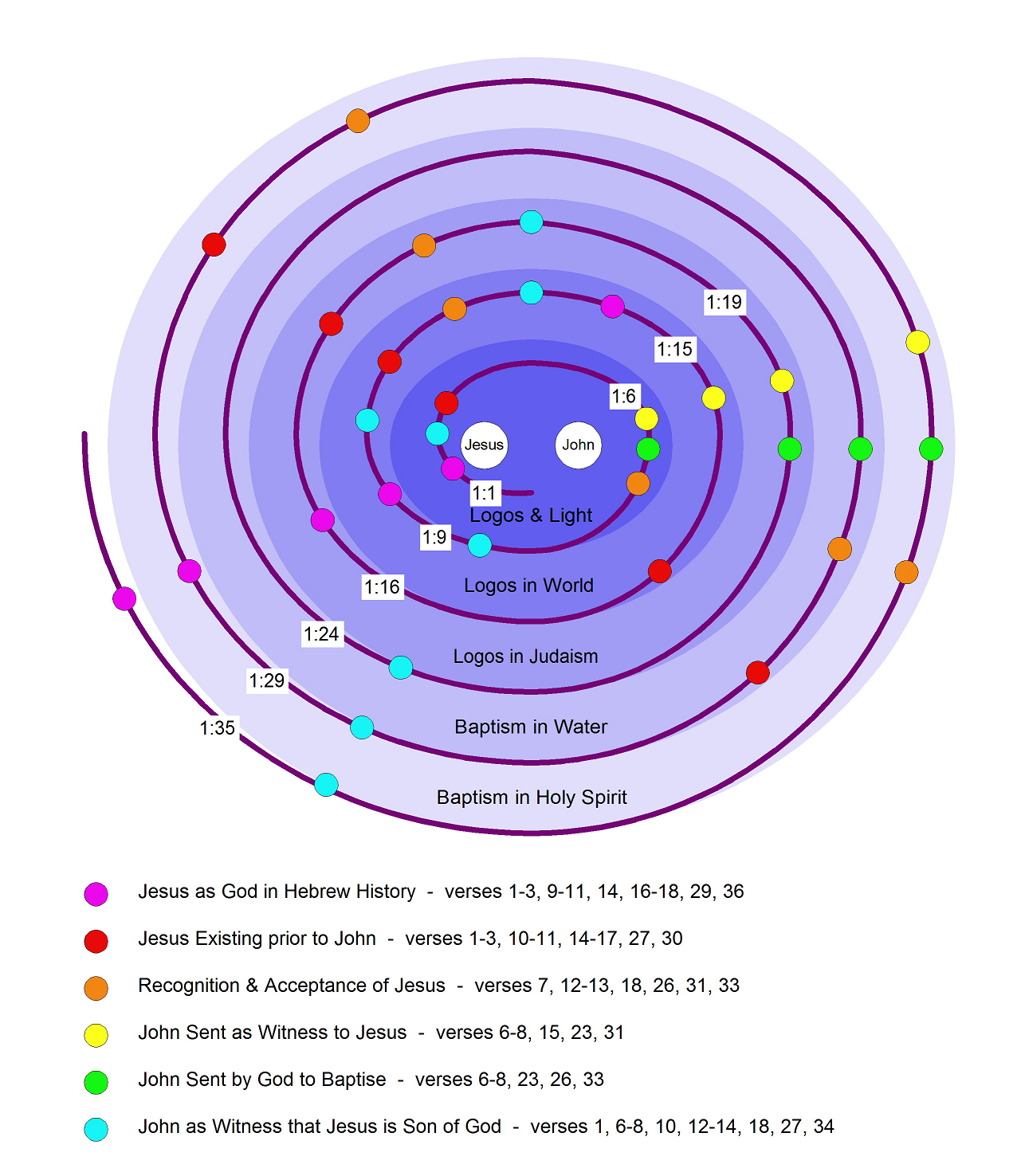

My assertion in this essay, then, is that the first chapter of John’s Gospel (at least up to verse 34) is also one continuous “spiral”, comparable to those in I John and John 6, which makes far more sense when considered as a single unit rather than as two separate sections (one a “Prologue” and one an account of John the Baptist). Like I John, John 1 is an “elliptical” spiral with two foci: Jesus and John the Baptist. Unlike I John, it is obvious that these two foci are not to be equated, and indeed one of the most important elements discussed is their difference. Let us therefore take a more detailed look at this passage in this light to see what might be revealed.

[Notes: I have adopted the convention in the following discussion of using the term “the author” whenever referring to John the Evangelist, and “John” only when referring to John the Baptist, simply as a means of avoiding confusion. This essay is not concerned with the actual authorship or dating of the Gospel, and no conclusion should be drawn from this usage regarding any answer to these issues.

For readers who are not familiar with Greek, I have included in braces a transliteration of the word into English letters, followed the first time it appears by the simplest common meaning of that word in quotes, for example: λογος {logos - “word”}.

I have chosen to use my own translation of this passage in order to bring out some of the nuances present in the Greek text, not as a replacement for other translations, but in order to complement them. It is therefore not intended as a smooth, readable, stand-alone translation, but one which seeks to highlight certain aspects of the original text often obscured when we read it in English.

In this light, the verbs γινομαι {ginomai - “to become”} and ερχομαι {erchomai - “to come”} presented a particular difficulty. The very common γινομαι {ginomai} can be a multi-purpose verb, covering meanings such as “to be created”, “to be born”, “to happen”, or even simply “to come”, and all of these potential English equivalents have traditionally been used when translating the first chapter of this Gospel. However, since the repetition of ideas and words is such an important technique for the author, such variation in translation seemed inappropriate in this case. It is striking how often, and at what critical points, the author employs γινομαι {ginomai} throughout this chapter, to the point that it seems that much of his meaning hinges on the subtle relationships between its various usages. So in order to help bring this across into English I have attempted in nearly every case where a form of this word appears to use an expression which includes the verb “to come”, such as “to come to be”, “to become”, “to come to pass”, or just “to come”.

This then made it difficult to translate ερχομαι {erchomai}, which normally means “to come” in the simple sense of physically “coming toward” or “arriving”, without the existential weight present (at least for this author) in γινομαι {ginomai}. To avoid confusion, I have here translated ερχομαι {erchomai} as “to appear”, which seems to adequately convey its meaning in this limited context.

Although I have divided this discussion into different “passages” which represent successive “passes” around the spiral, to help illustrate when certain themes are likely to reappear, these are slightly arbitrary divisions and certainly do not represent logical “segments” or paragraphs, since it is the continuous flow which is important to the author, and logical pauses may occur at any point around the spiral.]

First Passage (John 1:1-8)

| 1 | In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was near to God, indeed the Word was God. |

| 2 | This was near to God in the very beginning. |

| 3 | Everything came to be through this, and without this nothing which exists has come to be. |

| 4 | In this was life, and the life was the light of humanity. |

| 5 | And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not encompassed it. |

| 6 | There came a person sent out from God whose name was John. |

| 7 | He appeared as a witness, to testify concerning the light, so that through him all might come to have trust. |

| 8 | He himself was not the light, he came only as a witness to the light. |

One of the distinctions which is commonly made between the “Prologue” and the rest of chapter 1 is that the “Prologue” deals with eternal truths, whereas the rest of the chapter begins to tell the story of Jesus’ life on earth. But such a distinction melts away if we look at the text carefully, for the entire chapter from the very beginning is bound inextricably to history and any “eternal truths” do not exist in an ahistorical sense, but only within the context of the history of the Hebrew people. “In the beginning was the Word” is a clear reference to the first few verses of Genesis, the λογος {logos - “word”} itself being intimately associated with God’s speaking as the means by which the universe was created. This is certainly true, regardless of whatever other layers of meaning may be intended for the λογος {logos}, and so the first verse of this Gospel is a statement about the creation of the world in time, not so much a statement about a transcendent eternity beyond the world.

One other conclusion which may be drawn from this reference back to Genesis is that the λογος {logos} for the author is not so much a “thing” as an “action”. It is God speaking, and that act of speaking out the universe is equated with what God is, but I will refrain from saying that it is what God is “in and of himself”, because what I am suggesting is that the author’s intent is something quite different from the Greek philosophical categories of being and individuality which we are so used to reading back into this text. (Such meanings may indeed be applied, but if we approach the text from a more Hebrew-oriented worldview, then those will be additional meanings added in, rather than the basic intent.) It is for this reason that I have chosen the slightly awkward “this” to translate both ουτος {houtos - “this one”} and αυτος {autos - “he”} in these first verses in order to slightly lessen the sense that either an object or a person is being referred to, but rather God’s action of speaking the Word.

All of this also means that when we get to verse 14, when the λογος {logos} becomes flesh, then here again what the author seems to be expressing is something about God’s thoughts, words, and actions taking a human form rather than the “normal” way we are used to thinking about this in terms of substance and eternal personhood. Again, this is not to say that such an interpretation is “wrong” (it is, after all, the way in which the creeds of the Christian community tend to express our understanding of the incarnation), but it is one which we as the inheritors of the Greek philosophical tradition can hopefully expand somewhat in order to understand the author’s depth of meaning.

The links to the Genesis creation story continue in the next few verses, especially verse 3 (where it is specifically stated that everything which exists came to be through the λογος {logos}), but also verses 4 and 5 which connect the λογος {logos} to the light (the first thing created by God’s word in Genesis). And although the act of creation may be lost in the mists of time, it is still treated here by the author (as well as in Genesis) as an actual event in time, not merely a vague philosophical notion. We are therefore not off in heaven somewhere in these first verses, but solidly on this earth as it is being created by God through the λογος {logos}. Likewise, the life, light, and darkness spoken of in verses 4 and 5 are not disembodied Platonic “forms” existing in some ideal theoretical realm, but are actual physical aspects of the universe we all inhabit here and now, and which affect us all continually.

I have translated the verb καταλαμβανω {katalambano - “to overtake”} in verse 5 as “encompassed” because I wanted an English word which could carry both senses in the Greek of “understanding” (getting one’s mind around something) and “overpowering” (by surrounding it). And in verse 7 I have used the word “trust” rather than “believe” to translate the verb πιστευω {pisteuo - “to believe”}, again in an attempt to lessen the impact of the Greek (and Augustinian) philosophical notion that belief is a mental activity rather than something which includes one’s entire being.

The transition, then, from verse 5 to verse 6 is not a transition from eternal truths into a single random point in history, but is rather a continuation and a focusing on the history which is already being presented. John is a unique figure, with a unique relationship to the “light” which is being discussed here: he is it’s witness (and we are to think of this word as though he were a witness in court, giving evidence). The author is telling us here that John’s very purpose is to “shed light” on the light itself. Indeed, the author is really saying that the very reason we know about what has been said in the first five verses is specifically because John has told us about it.

These first five verses, then, are not an abstract theory presented by the author, but rather convey the content of John’s own (legal) testimony. We don’t know about the light, the λογος {logos}, through philosophical contemplation, but because of John’s testimony. Indeed, the entire first chapter of the Gospel is all about John’s testimony (not the author’s), and by reading it in this way it all holds together as an integral whole.

But one of the author’s main concerns throughout the chapter is to emphasise that John “himself was not the light”. This will be repeated over and over again. We may legitimately ask why this is of such concern: Is the author responding to proto-Mandaeans who did believe John to be the Messiah, or is he counter-acting Gnostics who believed that each of them had his own light? The answers to such questions are far beyond the scope of this essay, but it is certainly a major concern of the author, since he maintains as one of his themes throughout the spiral of this chapter the thought that John is in no way equal or comparable to Jesus.

Second Passage (John 1:9-15)

| 9 | This was the true light, which enlightens all humanity, appearing in the world. |

| 10 | He was in the world, indeed the world came to be through him, yet the world did not know him. |

| 11 | He appeared in his own place, but his own people did not accept him. |

| 12 | Yet whoever did accept him, who trusted in his name, to them was given the ability to become children of God, |

| 13 | coming to be neither from flesh and blood nor from man’s will, but from God. |

| 14 | So the Word became flesh and encamped among us, and we perceived his glory, glory as the only begotten come from the Father, full of grace and truth. |

| 15 | John testifies concerning him - and he has cried out saying, “This was he of whom I said, ‘He who appears after me has come ahead of me, in that he existed prior to me,’ - |

With verse 9, then, we have completed one circuit of the spiral and have now returned to focusing on Jesus himself rather than on John. But this is not focusing on Jesus apart from John in an abstract way, but rather focusing on what is the content of the testimony of John about Jesus as the light. It is as much John as the author, if not more so, who is telling us that Jesus was already in the world, and all the rest. This is particularly obvious when we get to verse 15, where John himself specifically says that Jesus “existed prior to me”, which only makes sense in the context of what is being said in verses 10 to 14.

Indeed, although I have not done so in my translation, I could have ended verse 8 with a colon and made verses 9 to 14 a direct quote from John himself. This would certainly not be inconsistent with other places in the Gospel where it is unclear where quotes break off and the author’s own comments begin, or vice versa. For instance, should verses 16 to 21 of chapter 3 be included as part of what Jesus actually said to Nicodemus, or are they a commentary by the author, expanding his speech? The answer may be that it really doesn’t matter. These verses express the truth of what Jesus was saying to Nicodemus, whether in quotes or not. In chapter 1, likewise, any verses which might be identified as the author’s own commentary are not in effect any different from what is being said by John.

[This addresses another aspect of the so-called “Prologue”, since it is usually described as setting out the themes which will be explored throughout the whole Gospel. But this would be true regardless of whether the content of this passage is attributed to the author or to John. For this author, truth is truth, and the same truth is expressed by Jesus, by John, and by the author himself. John’s testimony is fundamental for this author, and if he uses John as his means to set out the basics of the whole truth of the Gospel, then this should not surprise us.]

So what is being said here by John or the author in verses 9 to 14 (as we might expect from the author’s spiralling style) is very similar to what was said in the first five verses of the Gospel: Jesus as the light (the λογος {logos}) was God’s means of creating the world, and is still present in the world giving spiritual light to humanity. But (as we should also expect) the author has also added some new themes into the mix: first, the theme of recognition and acceptance of the light, and second, the resulting new creation which enables humans to become children of God. This is particularly significant since it is linked to the complementary process as well: God himself becoming a child of humanity (in verse 14).

It is in these verses that the author’s use of the verb γινομαι {ginomai - “to become”} is especially striking. All of the being born and becoming and being created here are all intertwined. Becoming children of God is therefore not simply some process we might go through (as Nicodemus is to learn later), but is an act of new creation on God’s part, just as dramatic as the original creation, and is effected in precisely the same way, by means of the λογος {logos}.

But the theme of recognition and acceptance (or the lack of it) is also very significant here, and again it is not a theoretical concept. It is directly related to what was said about John in verse 7. John gives his testimony so that people might recognise, accept, receive, and come to trust in the light. The trust in verse 12 is a direct result of verse 7. Those who believe do so as a result of John’s testimony. And those who do not recognise and accept the light are not just rejecting the light, they are also rejecting John’s testimony. Again, the entire flow of the text is totally integrated, even when it appears that the author is dealing with different topics.

I do not particularly care for the word “encamped” in verse 14, but it seemed the word most capable of conveying the sense of the word σκηνοω {skeno’o - “to dwell”}, particularly in its connection to the Tabernacle where God was a living presence (and certainly “encamped”) among the Israelites in the desert. The author has used a fair amount of poetic language up to this point in reference to the Hebrew community without naming it specifically. In verse 11 he tells us that Jesus went to “his own”, τα ιδια {ta idia - “the own”}, (plural, neuter, literally “his own things”), which might mean his own home, or his own “homeland”, which I have simply translated as “place”, but the reference is clearly to the Hebrew community, to the land of Israel. But he was rejected by “his own”, οι ιδιοι {hoi idioi - “the own”} (plural, masculine, “his own people”), God’s own people, the people of the covenant. By using such subtle language, the author is not moving from generalities or universals to specifics, but is beginning in a bit of a mist which slowly clears, and by this means the light is revealed.

Verse 15 here is, of course, the critical verse for us. Is it an interpolation and an interruption, or does it belong here? To answer this satisfactorily, we will need to look at verse 16 (and the rest of the context of this chapter), but before we do, let us look at how verse 15 functions within our spiral. I have suggested that the entire chapter spirals around two foci, Jesus and John, and as such we would expect it to alternate its emphasis back and forth from one to the other. If such a pattern is being followed, then we would expect to return to John at precisely this point. If the author had not done so, then the pattern would have been broken, and there might potentially be some justification for separating the “Prologue” from what comes after (although verse 30 will prove that such a division is impossible). In terms of the spiral, then, verse 15 is not an interruption at all, but the expected shift of focus which will enable the new themes to be considered from all their angles. And hence, here John comments on his own relationship to the already-existing light, that although John appears to be “before” Jesus (having been born earlier), he is actually of lesser import, but more than that actually came into existence after the existence of Jesus. The priority (πρωτος {protos - “first”}) of Jesus is fundamental to their relationship. If the author is following a spiral, then verse 15 is very important for maintaining this focus.

Third Passage (John 1:16-23)

| 16 | that from his fullness we have all received grace upon grace, |

| 17 | and that whereas the Torah was given through Moses, Grace and Truth have come to be through Jesus the Messiah. |

| 18 | No one has ever seen God. It is the only begotten God who is in the bosom of the Father who has made him known. |

| 19 | And this is the testimony of John when the Jews of Jerusalem sent priests and Levites to question him: “Who are you?” |

| 20 | And he admitted, he did not deny it but admitted, “I am not the Messiah.” |

| 21 | So they asked, “What then of you? Are you Elijah?” And he said, “I am not.” “Are you the Prophet?” And he replied, “No.” |

| 22 | So they said to him, “Who are you? We must give an answer to those who sent us. What do you say about yourself?” |

| 23 | He affirmed, “I am a voice calling out in the wilderness, ‘Make straight the way of the Lord,’ just as Isaiah the prophet said.” |

Verse 16 begins with the word οτι {hoti - “that”}, which I have translated as “that”. It indicates that verse 16 does not begin a new sentence, but is a continuation (as a subordinate clause) of what has come before. It is therefore a very odd place to begin a new “passage”, but if the author is following the spiral I am suggesting, then this is the point at which he begins another “lap”, since the focus is once again on Jesus.

The question is: Does verse 16 continue the thought of verse 14 or of verse 15? If we were to remove verse 15, then the sequence certainly would make sense. Verses 14 and 16 would then read: “We perceived his glory, glory as the only begotten come from the Father, full of grace and truth, in that from his fullness we have all received grace upon grace.” In this light, verse 15 definitely looks like an unwelcome interruption. Might it have been added by a zealous copyist who also recognised the author’s spiralling style and decided that John needed another mention here, or could it possibly have been a mistake? Either way, we are hard pressed to find a legitimate reason for inserting this verse into the middle of an existing sentence (and of course there were no verse divisions in the text at that time), if it is so unrelated to the content being discussed. To simply suggest that it is an interpolation therefore does not answer anything. It simply raises the question: How could such an interpolation have been inserted here?

The alternative is that the author intended verse 15 to be here, and that verse 16 is a continuation of its thought. But does such an interpretation make sense? Indeed, it does! John’s statement (here and in verse 30) that Jesus existed prior to John (even though John was born before Jesus) cannot stand on its own. It makes no sense for John to claim that although Jesus comes after him, he existed before him if John makes no reference to what it means to say that Jesus existed before him. (Later in the Gospel when Jesus makes unusual claims, these are always challenged by those who hear him. No such challenge is raised here.) If we try to separate the content of the “Prologue” as the author’s own comments about Jesus from the account of John’s testimony regarding Jesus, then we are left with just such a situation. John would be making an absurd claim about Jesus in verse 30 with nothing to back it up, while (as if in a bizarre coincidence), the very proof he is looking for is there over and over in the author’s “Prologue”: Jesus is the pre-existent Word of God who has been present throughout history, and particularly Hebrew history.

But if we read all of the content of the “Prologue” as being a summary of John’s own testimony about Jesus, then the whole progression makes perfect sense, as does John’s claim about Jesus existing prior to himself. Specifically, it makes perfect sense for John to make this claim precisely at the point of verse 15. John has “testified concerning the light” that it has become flesh and lived among us, and hence he can say in effect in verse 15, “this is why I said that he existed prior to me”, and then continue in verse 16 by saying, “since we have all received the blessings he has already given us”. Verse 15 is therefore not an interruption of the thoughts in verses 14 and 16, but a clarification that this is not something new which never existed before, but something which has already been here among us all along, and that John is corroborating this truth. Without these connections, verse 30 specifically will make no sense whatsoever. The resumption of the themes of grace and truth in verses 16 and 17 from verse 14 with extra clarification in between is typical of the author’s style, as the brief examination of John 6 has shown, and is certainly not an indication that verse 15 does not belong.

Grammatically, there are a few oddities here which must be dealt with, however. The use of the present tense in verse 15 followed immediately by the perfect (literally “John is testifying and has cried out”) is slightly unusual. Shifts in tense between past and present actions were not themselves unusual in Greek, particularly when a story is being told (or even in English, and indeed, to prove the point, I have just made such a shift myself in this sentence), but such shifts would normally be between a general present to a general (aorist) past tense and may often be ignored. Here, though, there is a bit of a contrast between the very general present “John is testifying” and the more specific Greek perfect tense which indicates something which has recently happened but its effect is still with us in the present. Indeed, the author has already made an identical shift in verse 5, contrasting the light which continues (perpetually) to shine as opposed to the failed (specific) attempts of the darkness to eradicate it. So here in verse 15 the shift in tense also seems to indicate that two separate things are being contrasted (but not in such a sharp fashion as the earlier example).

In addition to this oddity, we are then presented with a string of “οτι” {hoti} clauses, one at the end of verse 15, then all of verse 16, then all of verse 17. Οτι {hoti} may be translated as “since”, or “for”, or “in that”, and it is often used to introduce an indirect quotation (“he said that such and such”), but a οτι {hoti} clause normally cannot stand on its own as a complete sentence, unlike sentences beginning with και {kai - “and”} or γαρ {gar - “for”}. However, one of the recognised characteristics of John’s style is that he does sometimes use the word οτι {hoti} in the same way as και {kai - “and”} without the connotation of it being dependent on what has gone before. So in this sequence, as it is typically translated, both the first and third instances of οτι {hoti} are interpreted as being dependent while the second (at the beginning of verse 16) is not. But this is a completely arbitrary decision on the part of translators which does serve to isolate verse 15, but which then requires the author to have used the word οτι {hoti} inconsistently within this one brief passage. It would be far better instead to interpret all three instances in the same way, and hence as each beginning a dependent clause.

I have interpreted this sequence, then, in the following way: The present tense “John testifies” indicates to us that his testimony is something which is alive in the present, whereas his act of “crying out” happened at one particular time. I have therefore separated the remainder of verse 15 out as a (parenthetical) direct quote which John cried out that one time. This includes the first short οτι {hoti} clause (“since he existed prior to me”), which relates directly to what John has just said. After this, the next two οτι {hoti} clauses I have interpreted as indirect quotes which relate back to “John testifies”. Re-arranging the clauses in English makes this much clearer. Verses 15 to 17 would then read: “Having cried out saying, ‘This was he of whom I said, “He who appears after me has come ahead of me, since he existed prior to me,” ‘ John is testifying concerning him that from his fullness we have all received grace upon grace, and that though the Torah was given through Moses, Grace and Truth have come to be through Jesus the Messiah.” [I have capitalised Grace and Truth here because uniquely in this verse they are listed with the article, “the grace and the truth”.] Re-arranging the clauses in this way, however, although clearer in English, breaks the symmetry of the spiral, so I have not done so in my translation.

Another alternative would be to include all of the οτι {hoti} clauses as indirect quotes: “Having cried out saying, ‘This was he of whom I said, “He who appears after me has come ahead of me,” ‘ John is testifying concerning him that he existed prior to him and that from his fullness we have all received grace...” Although the sense here is virtually the same, the weakness is that it would be unusual to use the word “me” in an indirect quote, and here I have had to change “me” to “him” in order to be correct grammatically in English.

A third possibility would be to ignore the shift in tense as referring to two separate actions, and translate each οτι {hoti} as “since” in succession: “John testifies and has cried out saying, ‘This was he of whom I said, “He who appears after me has come ahead of me, since he existed prior to me, since from his fullness we have all received grace upon grace, since the Torah was given through Moses, but Grace and Truth have come to be through Jesus the Messiah.” ‘ “ In this case verses 16 and 17 would be part of the direct quote from John, not an indirect one. Any of these translations, however, (although some are awkward in English) make more sense of the use of οτι {hoti} than does the theory that verse 15 is an interpolation, in which case και {kai} or γαρ {gar} would seem more appropriate at the beginning of verse 16. And the weakest translation of all here would seem to be the one followed by most modern English versions, ignoring the shift in tense and treating the beginning of verse 16 as a new sentence. The Greek syntax here therefore strongly supports the inclusion of verse 15 as being original, and verses 16 and 17 being attributed directly to John’s testimony, either as a direct or an indirect quote.

One additional odd characteristic of verse 17 may also add weight to the idea that it was intended as part of a quote by John. The name Ιησους Χριστος {Iesous Christos - “Jesus Christ”} only appears twice in the entire Gospel, once here and once on Jesus’ own lips during his “High Priestly Prayer” in chapter 17. The author seldom seems to be arbitrary in his choice of words, and the usage of this full appellation “Jesus the Messiah” at these two critical points, once by John and once by Jesus himself would therefore make sense.

Regardless of whether verses 16 and 17 are to be considered indirect (or direct) quotes from John, however, they are certainly not to be separated from the content of his testimony. Verse 30 especially requires some reference to Jesus having existed prior to John, and this has been supplied from verse 1 up through verse 16 (but never directly referred to beyond that verse). Here again is ample reason for verse 15 occurring where it does, so that once we do get to verse 30 we will remember what has been said about Jesus’ pre-existence, and how John himself has already referred to it.

If, as some suggest, the “Prologue” had been added to the Gospel at a later date (with or without verse 15), then verse 30 would have been completely meaningless and incomprehensible in the original version of the Gospel. It’s only reference is to the existence of the λογος {logos}, identified as Jesus, at the creation (and the implication of his continued presence in Hebrew history), as recounted in these opening verses. Furthermore, John could hardly here be basing his testimony to the priests and Levites (that Jesus had existed prior to himself) on the thoughts of an author who would be writing his Gospel decades in the future. We must assume that (according to the author) John already knew, and (again, for verse 30 to make any sense) had already told his questioners the content we now read in the opening paragraphs of the Gospel, otherwise his listeners would also have had no idea what he was talking about. Verse 30 therefore provides clear proof that the author intended his opening paragraphs to be considered part and parcel of the content of John’s testimony about Jesus.

So, if we accept verses 16 to 18 as related specifically to John’s testimony regarding Jesus, we would expect these verses to once again pick up on some of the themes from the previous circuits around the spiral, and of course this is what we find. We have grace and truth again, we have the implication that Jesus has been present throughout the history of the Hebrew community, we have a restatement of how near Jesus is to the Father, and we have yet another instance of recognition, but this time it is Jesus himself who is making the Father known rather than John making Jesus known.

The new element this time round the spiral is the now blatant relationship of Jesus to the Hebrew tradition. Jesus is not only finally referred to by name, but he is also identified as the Messiah, and he is compared to Moses, whom he clearly surpasses since he is the “only begotten God”. The critical word here, μονογενης {monogenes - “only begotten”} is yet another variation of the author’s use of γινομαι {ginomai}, and is the only point in the translation where it was impossible to incorporate the English word “come” in order to make that connection. The word μονογενης {monogenes} here, and earlier in verse 14, could simply be translated as “unique”, “one of a kind”, “sui generis” (to use the Latin equivalent), if the author were simply content to let γινομαι {ginomai} be an all-purpose verb meaning “to happen” in various ways.

But the author’s use of the word throughout as a means of carrying the weight of creation and existence means that something far more powerful is going on here. It indicates that Jesus is unique as the only one who has “come into being” from the Father, but not meaning “created” by the Father, since that would not be unique, but to have “come from the being” of the Father, in which case “begotten” is the only English equivalent capable of carrying that weight. The other critical element here is that the earliest manuscripts, rather than saying the “only begotten Son”, say the “only begotten God” at this point. This is an unequivocal, powerful statement about the identity and nature of Jesus.

Verse 19 now harks directly back to verse 15 and complements it. Verse 15 tells us that what follows is John’s testimony concerning Jesus. Verse 19 tells us that what follows is John’s testimony concerning himself (not just John’s testimony in general). Even the verb tenses confirm this, since both these verses begin in the present tense. Verse 15 tells us that “John testifies”, not testified. Verse 19 says that “this is the testimony of John”, not that this was his testimony. In both cases, this is incongruous with what follows, but serves to mark the beginning of the respective testimonies.

In this context, too, verse 15 makes perfect sense precisely where it is. It continues the author’s spiral and leads into a discussion of the relationship of Jesus to the Torah and the entire Hebrew tradition. Since this tradition is the new element this time round the spiral, it is therefore important for the author to then continue in verse 19 (when he shifts from his focus on Jesus to his focus on John, as he has done in each earlier circuit) by placing John in his proper context within this tradition, just as Jesus has been placed in his.

In verse 17 John has told us that Jesus is the Messiah. In verse 20 he tells us that he himself is not the Messiah. The author has clearly juxtaposed these two statements deliberately, to once again compare Jesus to John. We are not suddenly in some different context here where John is answering questions about himself independently of his testimony concerning Jesus. We are precisely where we would expect to be by following the author’s pattern: in the second half of the spiral, picking up the same themes as in the first half, but related to the second focus.

Nor have we suddenly moved from eternal truths into a specific historical moment. Rather, we have really been at this moment all along, but now the mists have cleared completely and we see exactly where we are (and have been): with John as he gives his testimony to the delegation sent from Jerusalem, who are interrogating him (and this is why his testimony all along has been a legal one). And so John’s answers about himself echo what he has said about Jesus: Jesus is the Messiah. John is not. Jesus is greater than Moses. John is less than Elijah. Jesus is the only begotten God. John is merely a voice calling out in the wilderness.

It is therefore not the case that the author is setting a new scene at verse 19, he is simply clarifying where the scene has already been set all along. This, too, is a typical Johannine technique, and again it has a direct parallel in chapter 6, where it is only at verse 59 that the author reveals that Jesus had said all these things in the synagogue in Capernaum. In chapter 6 it is obvious that verse 59 is telling us that we have been in the synagogue throughout this dialogue, we have not just entered it. In exactly the same way, verse 19 of chapter 1 informs us where we have been all along, with John giving his testimony to those sent from Jerusalem, not that this is a new scene and a new dialogue beginning.

There is hence no logical break between verses 18 and 19 whatsoever. Verses 15 to 18 tell us this particular round of John’s testimony about Jesus. Verses 19 to 23 tell us John’s testimony about himself, in perfect symmetry. This point cannot be over-emphasised. Verse 18 flows perfectly and uninterruptedly into verse 19 with the subject matter in perfect balance!

But things are now about to change. Now that the author has gotten us to this point, he is ready to move on. The spiral will continue, but the contrast between John and Jesus will no longer be in alternating passages, but will rather become more intertwined and mixed together. This does not represent a change in the author’s style, but only a slight change of focus. (To maintain the geometric analogy we might say that as the spiral widens we see the two foci drawing closer together.) Indeed, the spiral will now resemble the one in John 6 more closely, since the author now has the freedom to reflect on any of the themes in relation to each other, not separating them into two “halves”. Instead of separating each pass into John’s testimony about Jesus and John’s testimony about himself, we will now have a single focus: John’s testimony.

Fourth Passage (John 1:24-28)

| 24 | Now they had been sent from the Pharisees, |

| 25 | and they questioned him and asked him, “Why then do you baptise if you are not the Messiah, nor Elijah, nor the Prophet?” |

| 26 | In reply, John said to them, “I baptise in water. Among you stands one whom you do not recognise, |

| 27 | one who appears after me, of whom I am not worthy to loosen the strap of his sandal.” |

| 28 | All this came to pass in Bethany across the Jordan, where John was baptising. |

This passage gives us one very quick spin around the spiral. The new element added in is baptism. Given the stark contrast of the last passage between Jesus and John, the author now deals with the question of John’s authority to baptise. John’s rather cryptic response (which will be made clear to his listeners in the next pass around the spiral, even though we as readers already know the answer) once again highlights familiar themes: Jesus is already present in the Hebrew community, but he has not been recognised, and Jesus is far greater than John.

Fifth Passage (John 1:29-34)

| 29 | The next day he watched as Jesus appeared, approaching him, and he said, “See, the Lamb of God who carries away the sin of the world. |

| 30 | This is the one concerning whom I said, ‘After me appears a man who has come ahead of me, because he existed prior to me.’ |

| 31 | And although I did not recognise him, it was so that he might be revealed to Israel that I appeared, baptising in water.” |

| 32 | And John testified saying, “I beheld the Spirit descending like a dove from heaven, and remaining on him. |

| 33 | And although I did not recognise him, the one who sent me to baptise in water said to me, ‘the one you see the Spirit descending on and remaining on him, this is the one who baptises in the Holy Spirit.’ |

| 34 | And I have seen it, and I have testified that this is the Son of God.” |

I have chosen to end this translation and analysis with verse 34, but the spiral actually does continue into verse 35, where John again identifies Jesus as the Lamb of God. But just as in John 6, the spiral becomes much looser from that point and then begins to lead away from John the Baptist altogether, so this seems a fitting place to end this discussion.

So, in the final major pass around the spiral, the author draws together all of the themes he has so carefully developed, in the light of the two final elements to be introduced: Jesus as the Lamb of God, and the activity of the Holy Spirit. The author has carefully led us to this single critical point: the baptism of Jesus (although the text here never does state that John actually baptised Jesus, but this also seems consistent with the author’s style elsewhere, since he also gives no account of the institution of the Eucharist, but does speak about eating Christ’s body and drinking his blood).

Jesus as the “Lamb of God” represents the ultimate way In which the λογος {logos} is God’s presence for his people in history, providing the eternal sacrifice for sins which fulfils the Tabernacle (going back to verse 14) and the whole Torah (verse 17). Jesus is also the one who baptises in the Holy Spirit, the means by which those who accept him become “children of God” (verse 12). This passage, then, gives us the culmination of all of John’s testimony in a very compact, condensed summary which contains nearly every theme discussed previously. This summary therefore carries with it all of the depth of meaning in everything which we have read from verse 1 onwards. Rather than going over each of these themes in detail again, however, the following table simply shows each verse in the present passage, listing the theme (or themes) with which it deals, and a list of the verses from previous passages where these themes have been mentioned:

| Verse | Theme | Previous Verses |

|---|---|---|

| 29 | Jesus as God present throughout Hebrew history | 1-3, 9-11, 14, 16-18 |

| 30 | Jesus existing prior to John | 1-3, 10-11, 14-17, 27 |

| 31 | Recognition and acceptance of Jesus | 7, 12-13, 18, 26 |

| 31 | John sent as a witness to Jesus | 6-8, 15, 23 |

| 32 | new material developing John’s testimony | |

| 33 | John sent by God to baptise | 6-8, 23, 26 |

| 33 | Recognition and acceptance of Jesus | 7, 12-13, 18, 26 |

| 34 | John as a witness that Jesus is the Son of God | 1, 6-8, 10, 12-14, 18, 27 |

As this table indicates, the present passage is intensely dependent on what has come before, and all of these links speak for themselves and need not be recounted again in this discussion. But such a densely packed set of allusions to ideas stated in the opening paragraphs of the Gospel therefore demonstrates that the idea of the “Prologue” having been added at a later date appears highly unlikely. In order for this to have been the case, several separate processes would have been required:

First, the original author of the Gospel (beginning presumably at verse 19) would have had no knowledge of the contents which would later exist in the “Prologue”. He would have been telling a simple story of John the Baptist’s activities, very likely based on Mark’s account, but adding cryptic elements about Jesus not being recognised, and existing prior to John. None of these elements would have been understood, however, since they are never explained later in the Gospel. (And indeed, if we consider the entire Gospel, then statements such as Jesus’ claim in verse 58 of chapter 8 that “before Abraham was, I am”, would likewise be without foundation and meaningless to readers if the Gospel had originally lacked its first 18 verses.)

Second, at some later date a different author (but basing his style on the style of the original Evangelist) wrote the “Prologue” (presumably without verse 15) as a general introduction to the Gospel. And although written as a general introduction, it just happened to supply all the answers to what John’s cryptic statements had meant. Not only that, it also happened to imbue John’s entire dialogue with the delegation from Jerusalem with amazing new depth of meaning.

Third, at an even later date, an absent-minded or over-zealous copyist either accidentally copied most of verse 30 into the wrong spot in the Gospel, in the middle of a sentence, adding incongruous Greek syntactical constructions in the process, or deliberately added verse 15 in order to make the passage match the spiralling style which exists elsewhere in the Gospel. Either way, by the single addition of verse 15, the entire first chapter of the Gospel, put together by two or three separate authors, suddenly and coincidentally came to reflect the same structure which the original author had employed elsewhere. This entire scenario does not seem to be a logical or adequate explanation for how the first chapter of this Gospel came to be written!

But what about the other possibility, that the “Prologue” (this time with not only verse 15 missing, but probably verses 6-8 as well) was originally written as a stand-alone hymn, which the Evangelist then used as the springboard for his entire Gospel, utilising not only its contents but its style as his own? There are several reasons why this is also highly unlikely: If the hymn had been written by someone else, then it would have been an amazing stroke of genius for the Evangelist to have based his entire literary style, as well as his understanding of the Gospel, on this one brief hymn. Additionally, there would also be the remarkable coincidence that the contents of such a general hymn about Jesus (without any reference to John the Baptist) would fit so perfectly into how the author would later develop the story of John (again, probably based on Mark’s account, and following the basic order of Mark).

We might suggest, however, that it was the same author who originally penned a hymn to Jesus as the eternal λογος {logos}, which he later decided to use as the opening for his Gospel, realising that it could be expanded in order to fit perfectly what he wanted to write about John the Baptist. But why would we need to suggest such a scenario if we acknowledge that we are dealing with one single author’s work? There would be no reason to suggest such a separate entity as this hymn which the author himself later reworked so efficiently to fill a different role.

By far the simplest solution, and the one which fits the content as explored in this essay, is that the author wrote his Gospel as is, knowing from the beginning how he wanted to expand Mark’s account of John the Baptist in order to show how Jesus is the eternal Son of God from the very first sentence.

There is clear evidence for this solution: The spiral style in Johannine literature is a demonstrable phenomenon which can be proved from passages such as John 6:25-59. It is not an artificial construction which I am trying to impose onto the present text. Chapter 1 of John’s Gospel fits this established pattern precisely, first as a two-focus spiral through verse 23, and then as a single-focus spiral to at least verse 34. The vast number of references present in verses 29 to 34 back to ideas expressed in the previous 28 verses demonstrates that all these connections (and hence all these verses) must have been in the mind of the author as he wrote verses 29 to 34. Additionally, only this solution adequately explains the content of verses 15, 30 and 31, as well as the unusual syntactical constructions in verses 15 to 17.

So, if we utilise the themes as presented in the table above, we can create a visual depiction of the spiral in chapter 1 as follows (similar to the spiral in chapter 6, but with two foci, Jesus and John, which for the first three passes divides the spiral into two distinct halves):

In conclusion, then, reading the first chapter of the Gospel according to John as a single, integrated discussion of John the Baptist’s testimony regarding Jesus makes far more sense than separating the text into two separate sections, one a general “Prologue” and the other an account of John the Baptist. No interpolations or separate stages are necessary to explain its writing, and the whole work holds together with remarkable consistency. This interpretation therefore seems to be far and away the most likely explanation of the author’s original intent.